The Accumulator, at Leeds International Pool

Posted: March 19th, 2008, by Daniel Robert Chapman

At the end of the nineteen-sixties Leeds proclaimed itself ‘Motorway City of the Seventies’ and opened an Inner Ring Road to connect the M62 and the M1. Edging the Inner Ring Road in the west end is a one-two of brutalist architecture which has defined the entrance to the city since that time but which will soon be reduced to one. The gritty concrete of the Yorkshire Post building, with its digital clock tower recently refurbished, seems secure; but the inverted black pyramids of the International Pool will be gone in a matter of weeks.

Like the claim to motorway supremacy, the ‘Central Baths’ have their roots in the once great city striving for new prestige in the post-industrial era. A pet project of the ruling Socialist Group of the late-fifties, the pool was to be of an Olympic standard and enjoy an international reputation. There was talk of holding a design competition, before a private sub-committee of the Leeds Corporation apparently arbitrarily appointed John Poulson as architect. They would say later that Poulson was just ‘the man you went to for everything at that time’. His firm, established in Pontefract in 1932 but eventually spreading as far as Malta, Lagos and Beirut, was just completing it’s first major project in Leeds – City House, a monumental office block placed above, and below, and within, Leeds City Station. In keeping with the new style of architectural practice his firm was pioneering, J.G.L. Poulson was appointed as “architect, structural, heating, lighting, ventilation and filtrations consultant in connection with the proposed central baths“. He also acted as quantity surveyor.

John Poulson had become the English sixties prototype of today’s ‘starchitects’, without ever even qualifying as an architect. He could live either in the mansion house of his own design, declared ‘House of the Year’ in 1958, or at his suite at the Dorchester Hotel. He was a millionaire, with growing political influence, welcomed in the higher echelons of British society; he owned a Rolls Royce, a Mercedes, and a Jaguar. His firm employed 750 people and held awards for the designs of several motorway bridges and flyovers, and had built public buildings and works throughout Britain. Hopes in Leeds must have been high for the construction of their new status symbol. Poulson was paid £109,000 for the design of an Olympic pool. The building, which cost £1.25m, was futuristic and flashy and was open before anybody could realise that it wasn’t Olympic.

A year later, in 1969, Poulson was declared bankrupt. In 1974, he was jailed for corruption, guilty of bribing government officials over the course of many years in a scandal which drew national attention. Poulson was described by the judge at his trial as “an incalculably evil man“ and sentenced to seven years in jail; while the city of Leeds was sentenced to forty years with an expensive swimming pool that wasn’t what it wanted, built by a man it must have wished had never existed – not to mention the monolithic City House.

The ‘Westgate Pool’ or the ‘Central Baths’, or the ‘International Pool’ did gain an international reputation, but not of the kind the idealists of the fifties and sixties had wished for. The true tale of how the Olympic Pool became merely the International Pool has been lost to playground folklore, the popular story in Leeds being that the hole for the main pool was dug to the Olympic standard size, but that putting the tiles on took a vital half an inch from each side, meaning it was unusable for Olympic competition and only suitable for International class swimming with temporary modifications. This may not be the real story, the Yorkshire Evening Post of 18th November 1974 stating enigmatically that “the pool, despite it’s cost, did not measure up to Olympic standards. It never had.“ What was more, the roof leaked and had to be replaced. The changing rooms leaked and had to be repaired. A construction company claimed costs of £120,000 due to a sub-clause of Poulson’s contract giving exclusive right of access to another steel contractor. Leeds Corporation filed a claim against Poulson in 1972 for £278,579, announced to him at one of his protracted bankruptcy hearings. The YEP reported that “Mr Muir Hunter QC, for the trustees in bankruptcy, told Mr Poulson to take a firm hold of his chair as he gave details of the claim“. Poulson declared it a ‘farce’, ‘ridiculous’, and ‘outrageous’, complaining of a bandwagon even when jail was inevitable. I can personally never remember a time when I wasn’t glad to live near enough to a decent suburban pool not to have to swim in town; the tales of cockroaches and unheated changing rooms were enough for me. There were serious plans for demolition as early as 1978; maintaining the building was costing £500,000 a year. It consistently escaped the wreckers, though, and the people of Leeds carried on swimming there; and driving past there; and looking down Wellington Street from there to City House, Poulson’s vertical assault on the city skyline towering over CIty Square; until the city could find a way to get rid of it all.

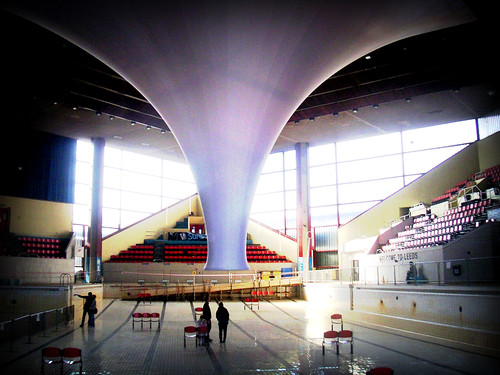

It was surprising, then, to stand last week on the floor of the emptied pool in the final days before its demolition, and look up at a major public art installation. The council’s reasons for supporting this project, beyond a general desire to be seen to do good, aren’t clear, and the results would probably not be to the taste of the old Leeds Corporation of the seventies.

‘The Accumulator’ takes the form of a giant canvas funnel, suspended from the ceiling and reaching almost to the deepest part of the drained pool. A person can stand underneath it and see steam billow within while ghostly sounds are played over the public address system. Apparently the original concept, by the Office For Subversive Architecture, had included cutting a hole in the roof to allow the pool to be refilled with rainwater and a number of live swans, but this didn’t happen, and the funnel is supposed to comment on sustainability, which doesn’t happen either. What does happen is that the scale and position of the funnel forces the viewer to take in much more of the pool’s architecture than they may have otherwise, and to reconsider it, and to almost be fooled into thinking that this was a good building after all.

Demolition seems almost spiteful when one is stood in the cleared central space. The building has always had an appealing retro-futuristic quirkiness. Externally it takes the form of two pyramids, one thrust point first down over the other. Glass enclosures form corridors around the intersection of the two forms, and a glass pyramid tops the building out (almost – atop the glass pyramid is a small stalk holding up a small silver ball, presumed to be a lightning rod and rumoured to contain some amount of plutonium). A tall concrete chimney to one side balances external concrete steps up to proposed ‘skyways’ which were thankfully never fully completed – a scheme of streets in the sky which afflicted a number of mid-century Leeds’ buildings (the former Bank of England building still has them) but which were never fully linked together. A square, decorated fitness block was flung at the side of the building and stuck. I have had visitors to Leeds stop me in the street and ask me what the hell this building is, pointing to the pool in the distance. Its sharp angles seem to turn away from you as you pass on the Inner Ring Road, its predominantly black finish stark against the red brick office blocks behind, the shape slowly revealing itself as you drive by.

Inside, the main pool space is defined by those two pyramids, the seats at each end rising to ungainly triangular points and the commentary box sitting square and unwelcome to one side. The four diving boards are part of the same sculptural concrete ‘X’, another triangular formation to one corner.

Before he died I should have liked to ask John Poulson what had taken him when he designed this building, or maybe, if he recalled who had designed it for him? ‘The Accumulator’s main achievement has been to draw heavy attention on to the pool building, so out of step with Poulson’s other work, leading to a positive reassessment and calls for it to be saved at this late moment. The Leeds Corporation of old would have sucked its teeth at the attempts a few years ago to have the pool listed, and would tap a ballpoint pen today on a pile of legal papers should anybody within earshot declare it a “brilliant place“. But by not providing any context or history to accompany the funnel, relying instead on local people and their memories of swimming lessons there as children, ‘The Accumulator’ has created an atmosphere of fond nostalgia which the International Pool, and John Poulson, do not deserve, and which obscures the more important lessons the pool could teach.

The unique futurism of the external envelope does not hide the fact that the place is built wrong. If Poulson did produce this shape himself, it would not have been unlike him to persist with it even though it did not create the Olympic Pool he was supposed to provide. For a supposed modernist architect, this is a win for form over function which should be enough to remove the pool from any modern conservation list. Leeds should not waste time trying to rescue a badly designed fluke that never worked and began to unravel from the moment the doors opened; that was not what was asked for or paid for and that was the product of one man’s life work in greed.

I would have liked to add a field trip element to ‘The Accumulator’, directing sympathetic visitors in nostalgic mood to walk down Wellington Street to City Square and look from there to City House. I think the destruction of the International Pool is justified if only because it will be many more years before Leeds can demolish City House – if it ever can. Poulson may have temporarily drilled into the city’s nostalgic hearts with the closure of his superficially attractive pool, but in 1963 he permanently bored into the shale strata far beneath the railway station and the river, and ensured that his ugly shadow would be cast long after the last stroke was swum at Westgate.

City House is a graceless stab at off-the-shelf International Style, a poor office block copied from a book and set deep into Leeds by a feat of civil engineering which renders it near impossible to remove. The two wings of the block straddle both a road and the railway, beginning a storey above the track and platforms of Leeds City Station; those tracks and platforms in turn are built above a complicated network of Victorian tunnels known as the ‘Dark Arches’ through which the River Aire flows. To allow City House to be built, concrete forms were sat on the shale at a depth of 35ft, drilled through the Dark Arches themselves. The structure is so integrating into the station that one wall of WHSmiths on the main station concourse is formed by a supporting pier of City House. To support the east wing, a 110ft steel table was placed over Neville Street, resting on four 50 ton concrete columns. These engineering works, which were admired internationally, allowed Poulson to then place his irremovable thirteen storey slab above a major point of entrance for the city, facing one of its most prestigious squares; no doubt earning Poulson a great deal of money and without any effort of thought on his part.

This is what anyone who, after visiting ‘The Accumulator’, considers the demolition of the International Pool to be a crime should go see next. City House is its own kind of exhibition, an exhibition of the damage that the kind of remorseless greed that drove Poulson can do to a place. The pool is an example too, but of a more subtle type, hiding its shortcomings in a futuristic and beguiling frame and a fog of nostalgic condensation. If cities have memories, then when it comes to remember Poulson’s pool Leeds should look to the nearby surviving relative and remember that the only shame was in being unable yet to demolish them both.